Technology makes our lives better. But there is a subtle line. Beyond that line, the constant assistance of technology in everything can be tricky. Marius Dorobantu, Postdoc Researcher & Lecturer in Theology & Artificial Intelligence at Vrije University Amsterdam, thinks that this can lead to a selfish perspective on reality, in which the world, technology, and even other people exist only to serve our needs. The ethical dimension of AI is currently the "hot potato".

Who bears the responsibility if a robot or an autonomous car causes material damage or even injures someone: should it be the user, the seller, the company, the programmer, or the government? How do we ensure that people have the last word in decisions that strongly affect human lives when it would be tempting to delegate such decisions to algorithms? I am referring to things like parole, credit lending, hiring, or deciding on medical treatment, says Marius.

These are essential questions on the road of technological evolution and society should answer them before developing AI myths and SF scenarios. We need a more balanced approach in order to understand the various AI applications on a case-by-case basis. In the following interview we talk with Marius Dorobantu about the current state of AI technologies and the ethical challenges of technology.

On the current state of AI technologies. Some of the benefits of AI. On the evolving relationship between creativity and technology

It isn't easy to objectively evaluate the current state of AI because our subjective expectations inevitably condition any assessment. Depending on how we set the standard for what qualifies as AI, we can reach very different and even opposite conclusions: either that computers are on the brink of reaching human-level intelligence or that we haven’t even made the first steps toward true AI. John McCarthy, the man who coined the term “artificial intelligence”, noticed that we only tend to regard as AI technologies that are futuristic, which we are not yet able to develop.

As soon as it works, no one calls it AI anymore; it is “just an app”. McCarthy was right. If we could transport forward in time people from the 1960s or even the 80s-90s and allow them to converse with Siri or Alexa, they would almost certainly think of such apps as true AI. We, contemporary people, are probably a little more skeptical about how intelligent such technologies really are. One thing is nevertheless apparent: true AI is like an ever-receding horizon, which moves farther as we try to approach it.

Everything I said so far concerns the notion of “true AI” or AGI (artificial general intelligence) or human-level AI. I began with this because AGI is the Holy Grail of AI; it is precisely what founding fathers – like McCarthy, Alan Turing, or Marvin Minsky – had in mind: the attempt to replicate the human intellect on artificial supports, in other words, the attempt to program a computer to do everything a typical human does. If this is the standard we have in mind, then AI seems to be still far away.

However, if we instead look strictly at what AI programs can do today, compared with a few years ago, then the progress is impressive. AI becomes surprisingly competent at increasingly more tasks that require intelligence when performed by humans. At first, AI programs only excelled at algorithmic activities, like mathematics or certain strategy games. As early as the 1960s, some AI programs were already capable of demonstrating mathematical theorems and playing chess at a decent level. Still, they quickly ran into trouble when it came to tasks that required flexibility, creativity, or intuition. In recent years, however, we’ve seen AI programs that seem to handle such tasks increasingly well, raising thus serious questions regarding some of the intellectual capacities we used to regard as typically human. I’ll only give two examples that illustrate the point I’m trying to make and are highly relevant for people working in the design/media/creative industries.

For more than 25 years, I’ve been a passionate practitioner of Go, a strategy game invented in China about four thousand years ago. In 1997, the AI program Deep Blue, developed by IBM, defeated the chess world champion, Gary Kasparov, sending shockwaves worldwide. I was a child then and had only learned Go the year before. I used to play against computer programs whenever I had the opportunity, usually in one of those “computer parlours” of the 1990s. Even as a relative beginner, I could easily win against the strongest Go programs because Go is incomparably more complex for computers than chess, even though it has simpler rules. The number of possible positions on a Go board is larger than the number of atoms in the observable universe, making it impossible for computers to calculate all possible variants resulting from a particular position. This technique is called “brute force” and is precisely the method used by Deep Blue to defeat Kasparov. At some point in the game, the giant supercomputer could simply calculate all the possible variants and choose the moves that led to a sure victory. This is impossible in Go because such a calculation would have to last billions of years, even on the most powerful current supercomputer. This is why the Go community was not too concerned with Deep Blue’s chess victory.

I remember the general mood being that an AI program could never defeat a Go master because Go is more similar to an art form than a logical task. Go masters don’t just make math calculations in their head; they speak of “feeling” what the good moves are due to an intuition developed in many years of study and practice. Furthermore, the esthetic and moral dimensions are arguably as important in Go as reason and analytic power. I mention esthetics because very often, masters are unable to explain why they made certain choices during a game; they can only refer to some visual harmony (that move “looked good”). The moral aspect is made apparent by the fact that a winning tactic always presupposes an ideal mix of character virtues such as patience, humility, courage, and temperance. Greed, arrogance, timidity, or pettiness, on the other hand, are usually detrimental.

Fast forward 20 years from the Deep Blue event and, in 2016, we have AlphaGo, an AI program developed by Google DeepMind, defeating Lee Sedol, a sort of Go’s Roger Federer, by 4-1 in a 5-game series. This event was a turning point in my life. I cried when the score became 3-0, and the AI’s supremacy became undeniable. AlphaGo was playing like a god descended among mortals, choking its human opponent with hopeless dominance. How was it possible for a software program to master a game that, when played by humans, requires such a complex combination of intelligence, intuition, creativity, and character? Without going too deep into technical details, the team at DeepMind chose to expose the program to tens of thousands of online games between top human players instead of “teaching” it what a good move or strategy is. This strategy is widespread in Machine Learning: the program learns by itself patterns by looking at many examples without being fed too much initial information.

Returning to the Go match between Lee Sedol and AlphaGo, it turns out that the real miracle was that Lee managed to win one of the five games. He achieved this through a genius move, called the “hand of God” by expert commentators. AlphaGo hadn’t even considered this move, ascribing it a likelihood of one in ten thousand! This would be the last time a human defeated a top Go program, with AI achieving complete supremacy ever since. It is interesting to note how the Go world evolved after this shock. Nowadays, top players carefully study the available human vs AI games and, even more, AI vs AI. From looking at these games, they rethink millennia-old principles and strategies. In other words, by observing these quasi-extraterrestrial intelligences playing against each other, we can relearn the game of Go in ways very different from what we thought possible. In my opinion, this is highly encouraging and can serve as a paradigm for other domains.

AlphaGo - The Movie | Full award-winning documentary

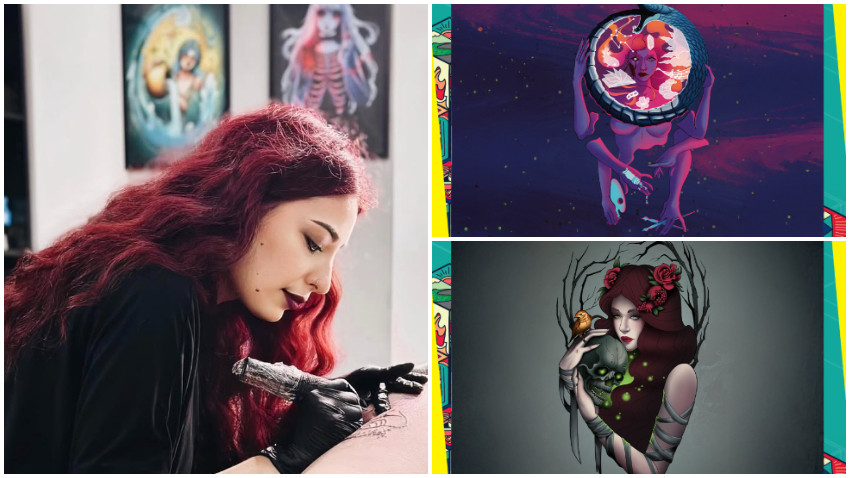

The other example I find relevant comes from visual arts, where AI becomes increasingly able to produce valuable and quality content. I had the privilege to receive early access to the newest and arguably most capable image generator, the AI program DALL-E-2, developed by OpenAI. I am completely fascinated by what I’ve seen so far. The user inserts a text prompt (a few words), and the program generates images that fit the description. Some pictures make no sense, but others are exceptionally good, especially when the user learns to speak the program’s “language”. The most exciting part is that the program can “paint” situations and objects that do not even exist in our world.

[A wolf posing proudly for his tinder profile in a forest at night, with a full moon in the background]

[Photo of a cat building a sandcastle on a beach]

Credit pictures: @DallePictures

I won’t get now into the debate on whether DALL-E-2 truly “understands” who Mona Lisa is or the notion of a cat in the same way that a human does. What I want to outline is that, through statistical and aggregation methods, AI is capable of generating such things. I first thought that DALL-E-2 signals the beginning of the end for many human jobs where people do precisely this: they create pictures on a particular topic for advertising campaigns, book covers, etc.

Suppose AI can already produce such results much more cheaply (OpenAI even offers a free subscription with a limited number of monthly credits). Why should most people choose to pay an expensive designer? But history teaches a different lesson, namely, that this is not necessarily the usual pattern for how technology transforms various domains, and certainly not the creative ones. As we discussed, AI is currently used in chess and Go as a source of learning and inspiration.

DALL·E 2 Explained

An even better example is what happened in the second half of the 19th century, with the advent of photography. Everyone thought that painters would lose their relevance. After all, why would you pay someone to paint an imperfect image of a landscape or a portrait when you can obtain a perfect image through photography? Nevertheless, the exact opposite turned out to be the case. The impressionist movement was born, and modern art would soon explode with unprecedented vigour.

I am hopeful that the same thing will happen now with the domains where AI achieves human or super-human competency: we will reinvent ourselves, and the result should be something more complex and beautiful than we can even envisage. But this also means we should pay attention to what is happening in AI. The first ones to figure out how to harness the new technologies will have an immense competitive advantage.

On how AI is being covered in the media

The media coverage of AI is highly polarized. I think this is because the public wants to read either that AI has almost reached the level you see in sci-fi or that AI can never reach such levels. This polarization can be observed in the reactions to the recent case of the Google engineer who claimed that the AI program he was working with (LaMDA) had “turned to life” and become sentient. He concluded this after a few conversations with the program that touched on existential themes. The public’s reaction was very polarized, with commentators clustering in two opposing camps. On one side, some believe or want to believe that we are just one step away from AGI. They regarded the Google engineer’s claim as proof of their belief. On the other side, some insist on pointing to the bizarre mistakes that AI (including LaMDA) sometimes makes, from which they conclude that there cannot be any real intelligence at work in these programs.

I think this polarized discussion is a red herring, distracting from the important facts: (1) that AI does make significant progress in various tasks/domains for which we, humans, use our intelligence, and (2) that deploying AI on a large scale, as it already happens in many fields, brings new, serious ethical challenges.

In my opinion, instead of discussing AI, in general, a more balanced and helpful approach would be to take various AI applications on a case-by-case basis. This way, we could better understand each program’s benefits and risks.

On the potential and limits of current hardware

Progress in AI has often been based more on quantity than on quality. I’m talking here about both the hardware and training data. Computing power has been consistently doubling every year and a half or so for the past half a century (the so-called “Moore’s Law”) due to our ability to cram increasingly more transistors on integrated circuits. However, we are currently approaching the physical limits of this growth. Transistors are becoming so tiny (of the order of nanometers) that it is quasi-impossible to shrink them further without getting unwanted quantum “turbulences”. What happens when we can no longer cram more transistors? This is an excellent question; from what I understand, we are not far from that moment.

I wouldn’t worry too much because we might devise ingenious solutions if forced to find them. There is talk of quantum computers or analog hardware instead of digital, which might be more suitable for artificial neural networks (after all, the “computer” we all carry on our shoulders is analog, not digital). Technological limitations push us to be ingenious and look for optimizations we didn’t even think possible. The reverse is also true: as long as we can keep adding transistors and GPUs (graphics processing units), there is a great temptation to become complacent and not look for better alternatives.

On people’s expectations regarding AI

In the long term, I would not bet against AI. I believe that once we’ve set our minds as a species, one way or another, we will complete this project as long as there are no metaphysical limitations. Here I step into familiar territory for me, namely, the theology of artificial intelligence. I think that AI is currently the most exciting phenomenon for someone who is deeply curious about existential or spiritual questions. This is, of course, not the only fascinating field. Cosmology asks compelling questions about the nature of our universe, its origin and destiny. Psychology and neuroscience likewise can shed some light on profound anthropological questions, like the relation between brain and mind, the ability of inert matter to produce subjective experience, or whether or not we have free will. All these questions are the bread and butter of philosophers and theologians, but progress in these fields is relatively slow. In AI, on the contrary, things seem to be happening very fast. It is my personal opinion that AI can provide new information that is relevant to the questions with which theology has been wrestling for centuries. I’ll only give one example.

Essentially, there are two possible scenarios: we either succeed in building artificial entities that are as intelligent or even more intelligent than us (something to be expected if we live in a deterministic-mechanistic universe), or we fail, for reasons that are currently mysterious (which might signify that human beings are more than just “complex biological mechanisms”). Whichever of these two scenarios turns out to be the case, I believe the philosophical and theological implications will be breathtaking. Our endeavour to build AGI is somewhat similar to our search for extraterrestrial life in the universe. Whether we discover that extraterrestrial life exists or find that we are utterly alone in this immensity of space and time, whatever the answer, it sends chills down the spine.

Coming back to the question about people's expectations, I guess both extremes are wrong: those who categorically reject the possibility of AI reaching human level and those who say that it is imminent and that in a few years we will have the so-called technological singularity. I think things are much more nuanced, and it will take significantly longer than some imagine until we can simulate human intelligence. Still, I would not reject this possibility in principle. It seems to me that the road to AGI is a bit like climbing a mountain: the mountain gets bigger as you get closer to it, but that doesn't mean you'll never reach the top.

What will AI be able to do in 5 years? What will it still be incapable of doing?

I don't think it would be very wise for me to jump into predictions because the history of AI so far has been marked by surprises. When everything seemed to be going well, and we thought we were just one step away from AGI, all kinds of obstacles appeared out of nowhere that led to relative stagnation and the dulling of the field's reputation (to the point where, in the 80s, most researchers and engineers were afraid to associate themselves with the AI label, because it was a sure recipe for being derided and not receiving funding). On the other hand, there were also moments when the majority predicted the end of AI, and that’s precisely when the field surprisingly took off again, achieving things categorized as impossible.

I suspect that self-driving cars will make significant progress in the coming years. Navigation is a highly complex problem that people like Elon Musk may have underestimated a bit. Still, constant progress is being made, and its accumulation should lead, in the medium term, to the quasi-complete automation of driving.

Another area where I think significant progress might be likely is personalized recommendations of all kinds, from entertainment to shopping. The more our existence moves online and, perhaps, into the metaverse, the more information we provide about our tastes and preferences through everything we do there. Thus, it shouldn't be very difficult for AI algorithms to refine their models about each user further and become capable of generating even more targeted suggestions and advertisements. The question is whether we really want such a world.

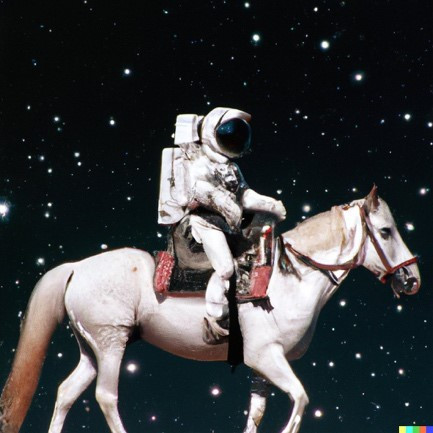

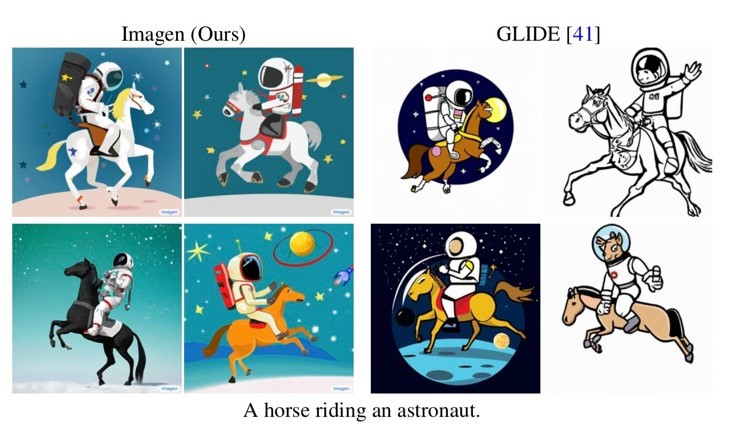

Something I don't think AI will achieve very soon is an understanding, in the true sense of the word, of the concepts with which the human mind operates. There are already chatbots that can converse convincingly, but they get woefully confused with specific trap questions. The same can be said about the programs that generate images from text, which I mentioned previously. They are impressive at first, but if you play with them enough, you see that they don't really understand much. Gary Marcus, a well-known AI expert, compared the images generated for "astronaut riding a horse" (which are spectacular) with "horse riding an astronaut". The latter shows that the system does not understand at all what is the subject and what is the direct object in the sentence.

[Astronaut riding a horse] (credit: @OpenAI)

[Horse riding an astronaut] (credit: @GaryMarcus)

I think this problem will remain unsolved for a long time in AI, and I doubt that the solution can come from simply more computing power or data. A completely new paradigm may be needed, one different from the current Deep Learning, which learns almost exclusively from (millions of) examples.

On the dangers of AI and how we currently handle the ethical challenges

The ethical dimension is currently the "hot potato" in AI. There are, in my opinion, both evident and subtle dangers. There is much talk about the obvious: how to ensure that algorithms do not inherit our biases (racial, gender, etc)? Who bears the responsibility if a robot or an autonomous car causes material damage or even injures someone: should it be the user, the seller, the company, the programmer, or the government? How do we ensure that people have the last word in decisions that strongly affect human lives when it would be tempting to delegate such decisions to algorithms? I am referring to things like parole, credit lending, hiring, or deciding on medical treatment.

Another urgent problem is that technology seems to accentuate economic inequalities instead of diminishing them. Some companies make huge profits due to their quasi-monopoly on data (just imagine how many pictures of human faces Facebook has), computational resources (who can compete with Google or Amazon Web Services regarding servers?) and talent. Is it right that these companies are the sole beneficiaries? Shouldn't AI be seen as a partially public good, given that we all participate, willy-nilly, in perfecting the algorithms through the data we provide whenever we do something online?

There’s an even more difficult ethical problem, which is being talked about more and more today: how much do we have the right to abuse and enslave intelligent robots, about which we cannot say for sure that they do not have the slightest bit of consciousness? Shouldn't we be extra careful and already grant certain rights to robots?

Among the more subtle dangers, I will detail only one: the hyper-profiling I was talking about earlier. The more information AI algorithms have about us (who we are friends with, where we like to go, what we eat, what types of posts trigger us, etc.), the better they get to "know" us and serve us more relevant and targeted suggestions. I think this is a slippery slope for two reasons. Firstly, it is a bit dystopian for algorithms to know us so well, sometimes even better than we know ourselves (as the historian Yuval Harari argues). I think that few of us would feel comfortable in such a world because it becomes unclear whether I made certain decisions because I wanted to or because I was subtly manipulated by all kinds of external forces, which most of the time try to maximize their profit at my expense.

Secondly, I don't know if it's good to completely outsource to algorithms so many decisions that concern us personally, even if it's about minor things, such as suggestions for shopping or entertainment. Such suggestions are often helpful, but if we end up being guided exclusively by them, certain capacities of our minds begin to atrophy. If you always depend on Google Maps, your orientation skills might suffer in the long run. Moreover, I think it is a bit harmful that technology, in general, and AI, in particular, be so much aimed at serving the needs of the individual. Let me be clear, it's very good that technology makes our lives easier, but I think there is an invisible line beyond which it can become too easy. The significant danger is that of infantilization. I might acquire a very selfish perspective on reality, in which the world, technology, and even other people exist only to serve my needs. If a website loading takes more than two seconds, I will explode with anger.

From this point of view, the way we treat the smart objects around us – today, bots like Alexa or Siri, but tomorrow, who knows, perhaps intelligent androids – can severely affect how we treat other people. And here I return to the topic of robot rights, a notion that some might find hilarious and others downright revolting and dangerous. It seems to me a possibility that should be treated more seriously, and this is not necessarily because these artefacts have any trace of consciousness or soul, but because by treating them with respect and compassion, we cultivate in ourselves very desirable virtues and practice a more humane way of treating other people.