Are we a mind controlling a body, or are our bodies essential to our sense of self and our understanding of the world?

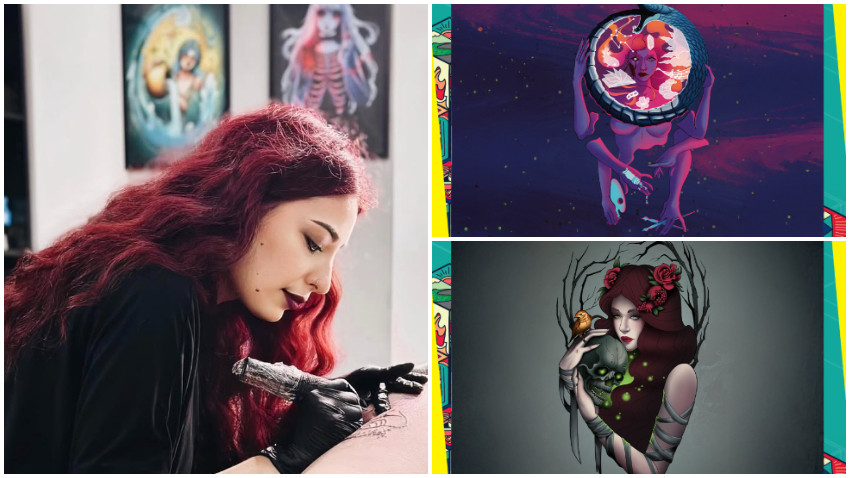

A creative entrepreneur known for her work at the intersection of sensory experiences, technology, and human connection explores the relationship between the physical and digital worlds, helping people rediscover their capacity to live authentically and in the present moment.

Grace Boyle is the founder of The Feelies, an independent studio that develops ways we can live multisensory stories in immersive contexts. With a master’s degree in chemistry and robotics, and a background in environmental activism and journalism, Grace uses innovative mediums to create experiences that encourage participants to connect deeply with their senses, emotions, and environment.

"I was quite academic at school, and I think without realizing it took on the dualistic notions inherent in an academic system, whereby everything can be thought through objectively and logically with the mind. I was disconnected from my body, and had to learn how to think with feelings as opposed to just with my head".

Grace Boyle is coming this year to the Unfinished Festival, which will be held in Bucharest, from September 27 to 29. Her work with The Feelies has led her to develop multisensory experiences in many countries and has been recognized worldwide.

We’ll be talking with her about stories for all the senses, artificial intelligence and embodied cognition.

Stages in your professional (trans)formation

Hello! I grew up in London, but spent my twenties as an environmental campaigner and journalist in India, which was an extraordinary privilege as I was able to witness the complexities of cultural ecology in a way which was radically removed from my upbringing. I actually initially studied chemistry - I have a master’s degree specializing in synthesizing materials that can be used to generate electricity from sunlight - but felt keenly that I wanted to leave the lab and engage with those topics in a way that was more physical, more human.

That compulsion for physicality - for sensorially - then became the underlying tenet for my work with my studio, The Feelies. Initially the studio made multisensory virtual reality pieces, and I worked for years developing how to use ‘multisensory’ as a medium for storytelling in that context. Rather than leading with vision and adding a smell or a vibration based on what you were seeing, I wanted to investigate perception, and how the different senses brought us different types of information, and different emotions. By working with sensory scientists, and treating the senses more equally, we experimented with a complex medium that could, perhaps, be used to communicate more complex concepts.

Of course, while virtual reality has headsets to deliver immersive visuals, there is no ‘headset’ for a bodily sensory experience. We ended up constructing immersive sensory architectures in galleries or museums to deliver our sensorial scripts, and developed devices to distribute scent in a way that permitted a changing narrative. I’ve been very lucky to work with an amazing range of talent along the way, from perfumers to programmers, and I love the ideas that can result from these kinds of unexpected collaborations.

More recently I completed another master in robotics at an architectural institute, which is a progression from these sensory architectures and ways of telling stories spatially. My study of sensory perception has also led me to be deeply interested in how we understand ourselves: are we a mind controlling a body, or are our bodies integral to our sense of self and our understanding of the world? If a robot is a technological intelligence inside some kind of body, then whether we understand intelligence through dualistic frameworks, or more as a phenomenon of embodied cognition, will be crucial to how we build our technologies. This is where my interests lie currently: investigating intelligence across digital and physical realms.

In the installation we’re creating for UNFINISHED, all of these seemingly disparate threads of my experience come together: chemistry, ecology, politics, technology, embodiment and intelligence.

The way you nurture your creativity

I’ve noticed a temptation to assume that one needs space to be creative - you know, ‘if only I could get some quiet time away…’. But in the pandemic, there was nothing but time, and I found it stagnant.

In reality, I find the opposite to be true - creative inspiration comes from being in dialogue with the world around you. Of course, I’m very lucky that there is ‘space’ in that to be creative in the way I’m interested in - I have a wonderful network of inspiring friends in scientific, engineering and art worlds, and get to travel often to take in other landscapes. And partnerships with others who also believe the work is crucial - working with the UNFINISHED team to bring this new installation to life has been amazing.

What inspires you

While I do love the physicality of materials, my work is mostly borne from concepts and ideas. I am intrigued by the edges of things, the gaps between things, be that different disciplines of study, or groups of people with different perspectives.

Looking back, the process is probably to research, learn and discover things I didn’t know existed, through reading, travel, conversations. That knowledge then sits in the background and comes back later - it may be weeks later, or years. What triggers it to come back, and fuse into a project idea, are emotions and human experience. It doesn’t come from sitting at a desk.

The idea of founding The Feelies

We made the first Feelies in 2014, as part of Shuffle, an arts / science / community festival in a wooded cemetery in east London lead by a small group of (mostly) women. It was founded by architect Kate MacTiernan; I was the Science Director. We put on all kinds of weird and wonderful things, like building London’s first treehouse restaurant as a way to explore symbiosis. One year I decided I wanted to make The Feelies. We cold-wrote to a leading VR studio, and to the Crossmodal Research Lab at the University of Oxford, to collaborate with us on the visual and sensory components, respectively. We took two existing pieces of audiovisual 360 content, and built them out into sensory rooms, based on crossmodal sensory research principles. I knew it was interesting, but I was unprepared for how emotionally impactful it would be for audiences to have a story fleshed out to multiple sensory modalities. I also knew that the way forward would be to treat the senses more equally, rather than adding sensory stimuli to existing visuals. Shortly afterwards, I founded The Feelies as a studio and began to work on creating stories that were multisensory from the initial concept stages.

The concept

The Feelies as a concept is actually from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, one of the great futurist novels of the twentieth century. He describes it as a multisensory cinema that people visit for entertainment - but in a dystopian society in which all extremes of feeling - pain, beauty, intimacy - have been eradicated to make a happier, more stable society. Of course, Huxley is deriding this notion, and his Feelies only show fluff stories to occupy time without provoking much thought. Our Feelies has mostly relayed stories of environmental or social importance, so I hope it does the opposite, but it was an interesting framework to start off with. And I certainly like the idea of provoking questions about how much of our experience can or should be delivered artificially.

Photo credit: Greenpeace / Fábio Nascimento

The experiences you want to continue to bring out into the world

In my past work as an environmental researcher and campaigner in India, I had observed the difficulties of trying to communicate stories of environmental urgency from rural areas, where they often occurred, to urban audiences, who were perhaps more socio-economically powerful but often disconnected from those far-off rural places. We were usually leaning on the internet as a way of campaigning, so this was a predominantly visual medium, and it could be challenging to cut through the noise of everything else on the internet and communicate emotionally.

When I started The Feelies, I realized that a multisensory medium could be a powerful way of communicating environmental narratives, not least because a lot of our comprehension of how valuable an ecosystem comes through the sensorial experience of being in a place - for example, the smell of rich, biodiverse soil, or the complexity of shadows formed by sunlight filtering through multiple layers of leaves.

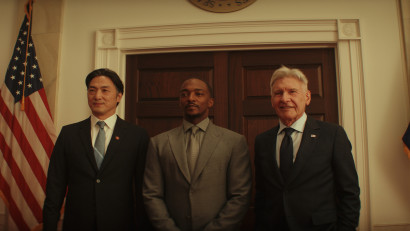

I took the idea to Greenpeace and we ended up creating a multisensory virtual reality piece in collaboration with the Munduruku, who are an Indigenous People of the Brazilian Amazon. The piece wanted to connect urban audiences, in Brazil and internationally, with the story of the Munduruku and build support for their efforts to protect the forest from mining, dams, and other destructive developments.

We spent some weeks living as guests of the Munduruku in the forest, performing a ‘sensory shoot’ of their lives there. All of the data and information we gathered was then worked into the story, in an artistic manner, and the piece opened to audiences in São Paulo for a month’s exhibition. I love the idea of making something which is intriguing and joyous for people to experience, but also carries a message of social or environmental importance.

The biggest projects involved in so far with The Feelies

Three come to mind; each in different ways.

The Munduruku project won awards internationally and has toured ten countries. It was released in 2017, and although projects incorporating technology can often age very quickly, people still present about it at academic conferences at leading universities, and write about it in their dissertations, which is a beautiful thing as it also keeps the story alive. Just this week someone wrote to me about featuring it in their doctoral thesis.

Photo credit: Greenpeace / Fábio Nascimento

On the fictional end of the spectrum, I worked with AR Rahman, an Oscar-winning composer and musical genius, in the conceptual stages of his directorial debut LeMusk, a cinematic sensory experience. He was very inspired by the notion of telling a story in multiple senses and is an incredible innovator, so it’s very special to work with him. Music and scent I think are far more similar media than visuals and scent, and you can feel a deep musicality in the way that he deploys perfume as a director. That premiered at Cannes XR and has shown across the world.

Lastly, I was the Sensory Director for We Live in an Ocean of Air by Marshmallow Laser Feast, a beautiful multisensory walk-through VR piece about the giant sequoia trees of northern California. We created four perfumes in a rising coordination with visual and audio senses, and a network of fans and scent devices to deliver them. It was the first VR to show in Saatchi Gallery in London, and was extended twice due to demand, before moving on to show in galleries internationally.

The value of collaboration with other professionals

Collaboration leads you to places and ideas that you could not dream up on your own, and to be able to have those unexpected experiences is, in my opinion, one of the great joys life has to offer.

I’ve probably worked with more scientists and engineers than artists, but most have artistic leanings and enjoy the opportunity to create something outside of what they might classically do in the day-to-day. In the UK’s academic system, and many others I’m sure, we’re encouraged to think of arts and science as separate fields… but I find it a very fruitful area for collaboration. And technology has done a lot to bridge that gap.

Most fulfilling experiences you've immersed into, to create stories that engage all human senses

Undoubtedly travelling to a remote area of the Amazon Jungle in Brazil to stay as a guest of the Munduruku people. I wouldn’t have imagined in a million years that this studio would lead me there – as I was saying above.

Another experience, ‘Dream Machine’, blended targeted dream incubation, artificial intelligence, and sensory stimuli to create an experience about the layers of consciousness. We built a local computational system in the unelectrified tower of a 13th-century castle in Poland as part of the College of Extraordinary Experiences. That involved running a 50m extension cable up by hand and then installing scent devices, a local network, AI, lights etc etc off this single plug point, which was an adventure! But the loft was such an evocative space, with thick, hundreds-of-years-old beams and incredible views over the surrounding countryside, that it was the perfect place to ask people to ascend and experiment with group dreaming.

Right now, I’m mostly excited about the installation at UNFINISHED - we’re sourcing these huge evocative rocks of salt from a salt mine a few hours from Bucharest, and a robot arm will sculpt it as a performance over the three days of the festival. The work is about biology and technology and asks questions about the differences and similarities between these two kinds of intelligence.

What fascinates you the most when talking about the human body, brain and senses

Investigating how we think and experience with our full bodies. I was quite academic at school, and I think without realizing it took on the dualistic notions inherent in an academic system, whereby everything can be thought through objectively and logically with the mind. I was disconnected from my body, and had to learn how to think with feelings as opposed to just with my head.

My work with Feelies introduced me to ideas of embodied cognition, and I find this physiologically and theoretically fascinating. For example, a concert violin player may be moving their arm faster than the time it takes an electrical signal from the brain to the fingers and back again. What’s going on there?

We talk about ‘muscle memory’ and ‘gut feelings’ so we do know, on some level, that we have thinking that goes on in and through our bodies. But it’s not part of a western ideology. Lately I have been intrigued by discoveries around fascia - it’s a web of innervated, malleable tissue throughout our whole bodies, and it’s received almost no attention from western science until just a few years ago.

Living in the AI era. How do you see it connected with art and human senses?

This is a very interesting question, because AI is an unembodied ‘intelligence’. It does have physicality - part of what the installation at UNFINISHED festival is commenting on is the mineral basis for technology and computation - but it has not developed its knowledge through having a body and being in the world, as we have. By this view, it can never be truly intelligent in the way that we are.

However, I do think AI has interesting potential for making our digital world a more sensorially complex place. To date, our digital realities have been dominated by vision, and a little audition, but AI has the computational power to handle a more complex integration of reality - if we are wise enough to be able to describe it.

In the physical world we all experience crossmodal perception, all the time - that’s our different sensory modalities mixing and influencing one another to make up our perception - but the general public still tends to think of our senses as separate. We also still think of the number of senses as being five, whereas we certainly have many more. We also don’t just perceive on the basis of a constant stream of sensory input, but rather seem do a lot of predictive processing - basing our understanding of the world on our expectations and previous experience.

So our journey of perceptual experience is incredibly complex - and digital worlds are currently a very poor sensorial environment. AI has the potential to make those digital worlds a much more complex, rich environment - if we are willing to feed it the right quality of information.

Of course, whether we want to feed information about our human senses to AI models that are owned by corporate entities is another question altogether.

Art evolution on the future

For digital art, I am excited by the possibilities that AI creates for screen-less interaction. Recently I’ve been playing around with ‘intelligent objects’ - using AI to give personalities to things in your surroundings that can interact with you in a dialogue that is generated in real time, and so different every time. The interaction could be through voice, as it’s a clear way to access the conversational sophistication of large language models, but it could also be through other sensory modalities.

Your presence at Unfinished Festival

Capucine and Cristian reached out to me and explained they were curating around a theme of praxis. It felt like a fortuitous connection as I had, only a few weeks before, found a thread of interest that I had researched obsessively: around the mineral deposits of Romania, and in particular the mineral streams, of which the landscape has an exceptional occurrence.

I was fascinated by the breadth of ‘types’ of mineral water that naturally occur in Romania and how in contrast that was to the sanitized view we have of water being just H2O. I loved the idea of water as a complex substance, imbued with the history of the rocks it flowed through. I also loved the way those minerals then passed into the cells of the people and animals who bathed in them - by being absorbed through the skin. To me, this is an illustration of our transversal connection with the world around us: it’s commonly taught that the skin is the edge of a body, and twentieth century modernism encourages us to think of ourselves as impervious individuals. But there are many things that extend out beyond the border of the skin: skin cells coming loose, molecules being breathed in and out, magnetic fields around the heart and brain that extend beyond the body. These boundary transgressions, for me, contain important understandings about the interconnectedness of life.

It’s also interesting to observe that many of the minerals needed for our biological health are the same minerals that are used to build computational infrastructure and hardware. It’s a complex situation as that includes clean energy technologies, which are essential for ecological health in our current climate crisis. As our demand for personal computing and other tech increases, I see a coming tension between the minerals required for biology, and for technology.

As AI gallops ahead, the boundaries between our biological intelligence and these technological intelligences are becoming blurred. One key distinction that remains is the ability of biological life to gather material from its surroundings and transform it into something else - re-generating flesh or hair; re-producing offspring. This is not something that technological or artificial intelligences can yet do. If the two need the same building blocks, who will win?

For UNFINISHED, we’ll be unveiling this new work I said before in this interview - an installation that unfolds over the three days of the festival, and explores these questions. It is raw praxis - machinery of manufacture hewing an integral form from mineral rock, in front of the audience’s eyes. It’s called re.source. Come and see it!

#Praxis. A personal perspective

Sensation is thought of as ‘truth’: you know something is real when you can touch it, hear it, smell it. Yet, we also engage with the world through predictive processing - we have a way we expect something to be, based on our past experiences, and in general we tend to be more comfortable when ‘reality’ matches up to those expectations.

Using a sensory medium for storytelling therefore presents some interesting challenges, because should you convey things exactly how they are, or how people expect them to be? We want to challenge people and to show them new perspectives, but we also want them to stay engaged and trusting in us.

For the Munduruku project, I remember when we arrived in the Munduruku village, in quite deep forest. Our Feelies team was me and a perfumer, Nadjib Achaibou, whose role was to be a kind of live data gatherer for scent. Immediately, he was taken back by the difference between how he had expected the jungle to smell, which would have featured a lot of the green notes they teach in perfumery school, and the reality, which contained a lot of rotten material in addition to the flowers, the green leaves. In the end, we ended up making a perfume that was somewhere in between - that took people away from their expectations, but not so violently that they no longer believed the story we wanted to tell them.

Your hopes for what the audience will take away from your installation at Unfinished

I think we’re living at an extraordinary and critical point in time, and it’s crucial that we engage in these big questions of intelligence, ecology and futures with all of our capabilities. Humans can be so clever, and have such impact. So I hope this installation will trigger some of that thinking in a way that inspires, and also provokes intrigue and pleasure.

For me, I hope to have many conversations with people at UNFINISHED to hear *their thoughts and stories - being able to present work to people like this, is such a privilege.