"I am daughter of a place / I am future mother of spaces". They are lines from a poem written in Martina Muzi's master's thesis, a kind of manifesto for her vision of design.

Martina Muzi curated the exhibition "Signals - Design is not a Dashboard", presented with FABER in Amzei Square, as part of Romanian Design Week. It is the culminating exhibition of the Bright Cityscapes program developed within the Timișoara 2023 – European Capital of Culture initiative and a collaboration between FABER and the Politehnica University of Timișoara.

"For myself and the team, the first step was about trying to understand how we see the city through our own lenses—our own eyes, our own knowledge, our own experiences—not in order to give answers, but to understand the methodologies and positions from which the project begins", says Martina.

Martina is the curator of the exhibition platform GEO—DESIGN at Design Academy Eindhoven, founder of the collective pedagogical research program Stigmergy and co-initiator of ArcHertz, an experimental sound program at Universo Assisi. As a member of the Space Caviar studio since 2014, he has led a variety of projects for the Venice Architecture Biennale, the Vitra Design Museum, the Interieur Biennale in Kortrijk and the M+ Museum of Visual Culture in Hong Kong.

We talk with Martina Muzi about the need for collaboration in design and how the role of creators is changing in the context of technological and social transformations.

If your experiences in design were to have chapter names

In between, In the field, In motion, In connection

How has your perspective on design changed

At the beginning of my design path I remember asking myself what are the possibilities for a young woman to participate in the design discipline, and soon while studying I started to think that maybe designing contexts to explore the possibilities of the design practice was a possibility itself. I remember that for my MA thesis I wrote for myself a poetry which became for me a sort of manifesto saying:

I am in the middle of a transition,

I am daughter of tradition,

I am future mother of knowledge.

I am in the middle of places,

I am daughter of a place,

I am future mother of spaces.

This short poetry accompanied me in the next steps of my career and to this day I keep it close to me, in my approach to curating as a designer in the middle of places, spaces and knowledge. Sometimes it is useful to go back to it as a ground from which to start projects and relations. Curating exhibitions is a framework in which research, practitioners, places, media and techniques meet. Throughout my career things evolved, for example design questions became more complex, contexts of work more tangible or intangible, design visions are sharper, however the understanding of my practice as a transformative process stays and this short poetry still represents the curiosity and constant search of design politics and possibilities.

Through my working experiences I had the opportunity to collaborate with a diverse group of talented and visionary people which opened up contexts of explorations and contributed in my own growth and understanding the different values and application of design. In the past years I had the chance to participate and develop field and contextual research during the making of projects finalised through different formats such as movies, exhibitions, workshops and installations. I had the opportunity to travel in different places and spend time in different cultures and geographies. Through the many projects and situated research the understanding of design expanded and my interest for systems, economies, societies and their gaps in between became more tangible.

Expectations & fears

Expectations and fears again bring me to the idea of possibility. Possibilities generally come with both expectations and fears, which are both valuable emotions within the growth of my creative practices and probably accompanying me along the entire process of work. In considering the concept of possibility, it's important to understand not just what can be done, but also how to engage with it, where to focus, and so on. This perspective transforms possibility into a goal or direction for engagement, or a scenario that emerges from viewing things differently. I learned this concept through my studies and work experience, and I believe it helps create a healthy coexistence of expectations and fears. Designing possibilities and fostering collaborative design are crucial concepts, especially when balancing expectations and fears in the workplace.

What has fundamentally changed in your relationship with design

What stays the same is the curiosity and the vision of the transformative force that design can have in society when it engages with it. What has been evolving is the understanding of the diverse and complex frameworks, models, materialities, technologies, collaborations and engagements that design needs to consider to operate and engage with the different aspects of society. While understanding that design participates in complex systems on which our everyday life takes place, it became clear that collaboration and bridging knowledge is essential.

Along my journey I experienced how important it is for design to operate at different levels, to name a few: from the school to the home, from the digital and physical space to the public realm, from industry to local or global markets, from included to excluded agents. For example the school is a place of learning and testing ideas; the studio is a space for researching and testing formats and potential application of ideas but also one of the possible business model to work; engaging in field research is a process for embodying, listening, speaking, expanding and sharing knowledge; studying markets, platforms and economies might open up question on the values through which design operates; exhibition spaces both institutionalised or temporary are valuable moments in which different typologies of design work can be activated and knowledge redistributed.

Your experience as a curator at RDW

Turn Signals - Design is Not a Dashboard, is the exhibition we presented with FABER at Amzei square as part of the RDW. Moreover, it is the culminating exhibition of the Bright Cityscapes program developed within Timișoara 2023 European Capital of Culture initiative and a collaboration between FABER and Politehnica University Timișoara. For the RDW, with FABER and its team we had the chance to make the exhibition travel from Timișoara to Bucharest and we reconfigured its outcomes on the ground floor of the market building. The space allowed us to present our research and approach to an extended audience, which is a fantastic opportunity not only to share our design questions with other designers but also with the larger public of the RDW.

My experience was shaped by the generous atmosphere of the network of designers and practitioners. Our project was welcomed with curiosity, openness and from a diverse public including students and experts in the design sector. For example I had tours with art students with whom we spoke about AI and creative thinking, inspired by the AI generated videography developed by Bianca Schick and Alex Foradori that responded to the economic report at the base of our research. Furthermore, the Bright Cityscapes book, which collects interviews with the designers and the main voices and parts of the program, sparked conversations with graphic designers and publishers about the role of publishing and the importance of documenting contemporary history.

During the opening time we had the chance to meet and exchange conversation with practitioners who work and live in Bucharest and to share with them the longer term design program we are developing at FABER. In fact, during RDW we had opened a call for Romanian designers to participate in the FABER upcoming design program which continues with the ambition of “Design Signals” and expanding design research and engagement with the local and national productive ecosystem.

While in 2023 we looked at the automotive industry which is the largest manufacturing sector in Timisoara, this year in 2024 we are engaging with the theme of the textile industry. There was great enthusiasm of both young and expert designers in getting to know more about the program. The exhibition space became in fact a conversation board to talk about the curatorial approach while the individual and collaborative projects of the designers in the show became a starting point to share and go deeper on design practices, media, technologies, landscapes and in fact possibilities for future collaborations.

The concept of the exhibition Turn Signals - Design is not a Dashboard

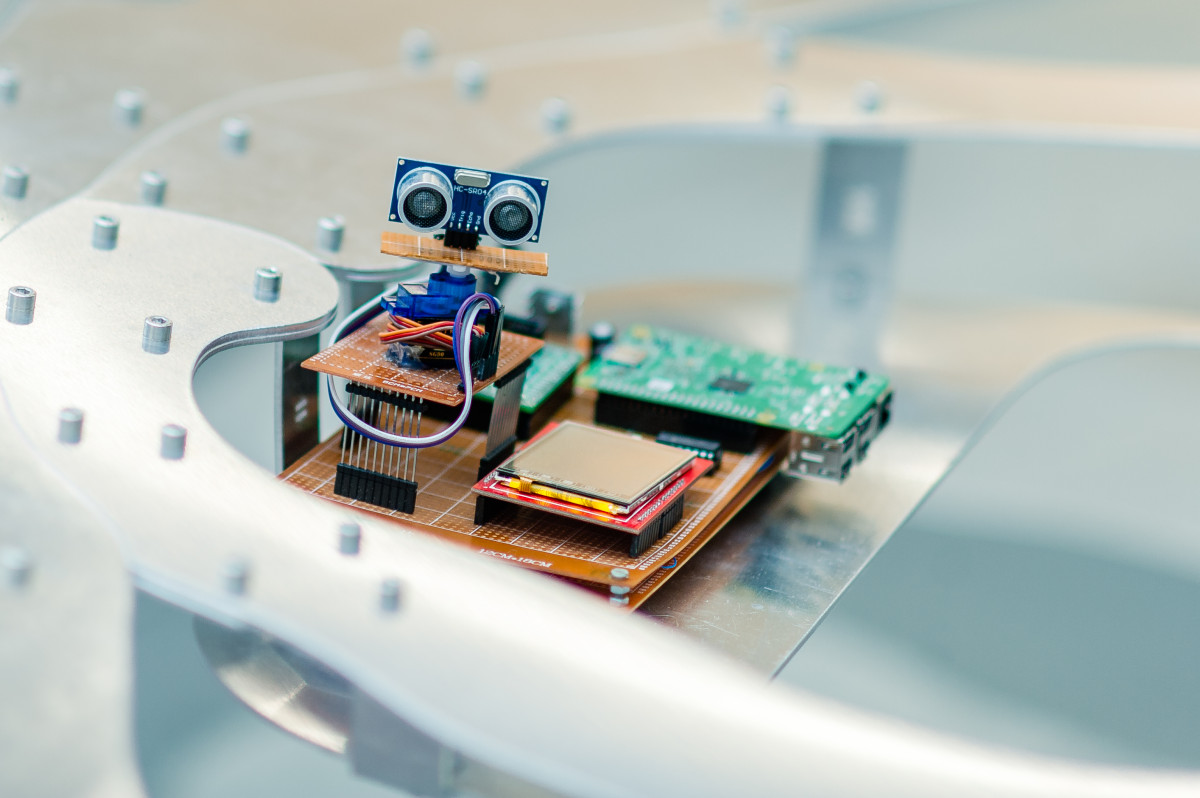

Turn Signals — Design Is Not A Dashboard is an exhibition that explores how design can act as a conduit for collaborative ventures that go beyond the confines of established manufacturing parameters. Anchored within the contextual framework provided by a commissioned report, ‘Economy in Timișoara: Territorial Distribution of the Economy in the Timișoara Metropolitan Area’ by Norbert Petrovici, the exhibition invited multidisciplinary practitioners to collaborate with local researchers, interpreting the statistical data through the designed lenses of devices, bodies, agents, media, forces, and networks. These collaborations drew from existing research, leveraged the local engineering network, and engaged with well-established knowledge systems within and beyond Timișoara’s industrial ecosystem.

The resulting projects converge at the crossroads of information asymmetries across disciplines, supply chain stages, computational processes, the collective imagination, material cultures, and the expansive manufactured environment. By observing and reinterpreting the navigational pathways of these asymmetries, these projects signal the presence, concealment, and imminent transformation of design within Timișoara.

The exhibition’s title draws inspiration from an indispensable everyday object produced in local and multinational automotive plants in Timișoara — the turn signal indicators on vehicles, used to communicate directional shifts to fellow drivers. These indicators, enmeshed within the intricacies of engineering processes and nestled onto dashboards, exemplify the potential for design to be limited to mechanical refinement and obscured by technological complexities. By exceeding the confines of a mere dashboard, the design practices and discourses in the exhibition have explored the city’s products and resources from local and global perspectives, connecting places, people, and urgencies across different scales. The exhibition serves as a turn signal to Timișoara, inviting a new trajectory for the city’s design, architecture, and digital culture.

Different media, storytelling formats, and design languages are used to explore both the hidden narratives and untapped resources within Timișoara, and how design can intersect with and question topics related to industry more generally. By dislocating the expected media and aesthetics of how the city is represented, the exhibition tells compelling stories that invite different ways of seeing, expanding imaginative possibilities. The participants are Romanian and international designers including: Versavia Ancușa, Théophile Blandet, Cinzia Bongino, Ioan Both, Nadine Botha, Cristina Cochior, Jing He, Raul Ionel, Flora Lechner, Guillemette Legrand, Alina Lupu, Petre Mogoș and Laura Naum / Kajet Journal, Simone C Niquille /technoflesh Studio, Parasite 2.0, Santiago Reyes Villaveces, Federico Santarini, Bianca Schick, Kirsten Spruit and Cristina-Sorina Stângaciu.

What were the challenges

I would like to respond to this question with a short travel in the journey that characterises the enriching process culminating with the Turn Signals - Design is Not a Dashboard exhibition, which I consider a beautiful project example of what possibly means to curate a process of engagement with a place while understanding the place as part of an economical, social and design network.

For myself and the team, the first step was about trying to understand how we see the city through our own lenses—our own eyes, our own knowledge, our own experiences—not in order to give answers, but to understand the methodologies and positions from which the project begins. To gain first-hand insights into Timișoara’s industrial ecosystem, we embarked on an adventure of visiting local factories. Visiting manufacturing environments physically with our bodies, and speaking to engineers, operators and workers, served to activate the process of engaging with local knowledge.

Simultaneously we initiated an interdisciplinary collaboration with data analyst and sociologist Norbert Petrovici. Through the collaboration, original research was done into how the city’s economy was formed, uncovering the major forces that have shaped its current state. By researching the economy of the city, so many different layers of the city are considered—the landscape, the climate, the everyday life of people, the jobs, and of course, the industries and the university.

The bridging of disciplines that went into the research report resonated with one of the core aspects of the programme: generating opportunities for research exploration and fostering exchanges. In particular, an open call was launched to UPT researchers who might have research within their labs that they wanted to share with a designer. From those that applied, four applicants were selected by an internal jury of representatives from FABER and UPT, and subsequently matched with international designers.

When selecting designers for the exhibition, it was important to invite practitioners who have cultivated idiosyncratic design practices and positions in order to challenge the programme, and expected notions of Timișoara and design. All of the designers worked with Timișoara as nexus, whether through a direct collaboration with a local researcher, whether through the research report as a guide, or whether by constellating particular assemblages of knowledge and partners. Some of the participants travelled to Timișoara for a creative research residency, allowing them to engage with the specific context and knowledge of the city. Others looked at how global phenomena manifest in Timișoara, Romania, or Eastern Europe. Others sought to establish a local connection or develop a local case study that furthers their existing research into particular concerns.

Between their diverse practices and divergent approaches, a large group of practitioners including myself engage with Timișoara in many different ways. The results portray the design discipline as a discourse that is constantly negotiating the relation between digital and physical practices, suggesting and emphasising a constant inquiry into technologies, materialities, archives, landscapes, and infrastructures, and their related narratives, applications, imaginaries, technicalities and unsolved questions. These are challenges that can be extended to the design discipline itself and therefore make for me of this exhibition a beautiful process between the challenges of curating within the complex systems of our everyday life while still grounding our practices to the reality and needs of a specific place.

The role of creators in the context of the social & technological transformations

For this question, I would like to share some design reflections which inspired the title: Turn Signals — Design Is Not A Dashboard.

The exhibition’s title provokes us to view design beyond mere process optimisation and mass-produced industrial solutions. Instead, it delves into design as a discipline for uncovering and manifesting hidden signals and opportunities for change, countering the dominating technocratic discourse. It highlights the potential found in the gaps and blind spots created by optimisation and standardisation. The projects address a myriad of thematics, such as the impact of global phenomena like outsourcing on local experiences and domestic scenarios, the import and export of knowledge as capital, the web of dependencies within global supply chains, academia’s role in knowledge production versus perpetuating standards, the effects of digitalisation and automation on daily life, working conditions, and the global economy, and more.

Here are some questions we shared with the designers and team. What if, when discussing digital infrastructure, we consider independent solutions outside of national frameworks? What if, when exploring automation, we also recognise the value of errors? What if, when examining imports and exports, we focus on waste rather than just freshly made products? What if we incorporate the perspectives of geologists when discussing hardware? What if subverting the linearity of supply chains can occur gradually through small inquiries?

Perhaps it’s time to direct our efforts towards understanding the inaccessible. Maybe it’s time for industries and institutions to recognise and support the explorations of independent design practitioners as essential to challenging perspectives and observations otherwise gridlocked by market demands. Part of understanding the significance of design as more than a discipline simply oriented towards optimising industrial products is also understanding design education not as an endeavour to only produce product makers. This is why in my own practice, design and education are so deeply intertwined.

Design and education is also fundamentally present in the design program of FABER in which a pedagogical impulse, to inspire re-analysis and reimagination of contemporary systems, extends to students from different disciplines, creating frameworks inside FABER. In my opinion, if we truly want to facilitate designers in addressing the complex questions of today, it is imperative to transcend the boundaries of curatorial, organisational, and design approaches. An environment that enables individuals to work next to each other within specific contexts while embracing diverse perspectives must be cultivated.