The 67th edition of the annual World Press Photo international exhibition can still be visited in Bucharest until June 7, at the University Square. Among the photographs that are exhibited, the public can see images that capture the effects of climate change such as: the drought in the Amazon, the fight to save the Monarch butterfly in Mexico, the drama of the first climate refugees in the United States, the devastating fires in Australia and the disastrous contamination of the Cileungsi River in Indonesia.

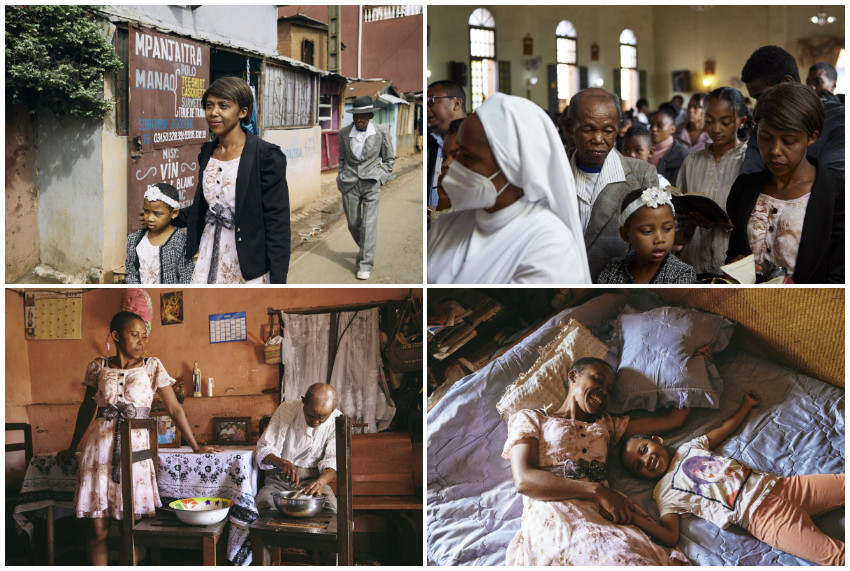

A project with a less resounding impact, but important for current times, is signed by Lee-Ann Olwage, who documented dementia for 3 years, in Namibia, Ghana and Madagascar. Her idea was to bring to show the role of superstitious beliefs and cultural meanings attributed to dementia, as well as the need of support for those living with dementia in Africa.

„Valim-babena” is part of a large project called „The Big Forget”. Lee-Ann Olwage won the 2024 World Press Photo Article of the Year Award with „Valim-babena”.

„The project Valim-babena forms part of a larger long-term project called The Big Forget. The project aims to understand the role of superstitious beliefs and cultural meanings ascribed to dementia to support those living with dementia in Africa”, says Lee-Ann

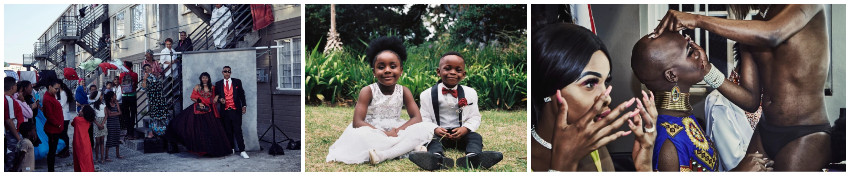

Lee-Ann Olwage is a photographer and storyteller from South Africa. In her work, she explores themes related to identity, education, health and other universal topics, all through long-term projects. Lee-Ann has also won awards at the 2023 and 2020 editions of World Press Photo.

About you

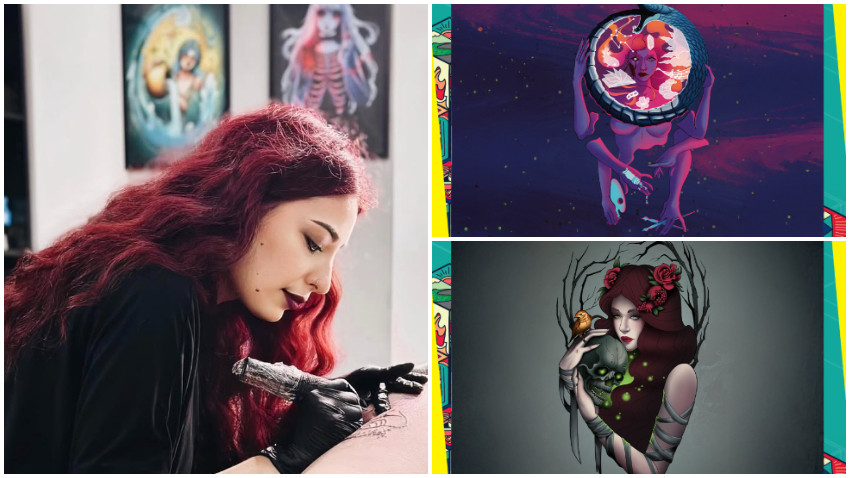

I am a visual storyteller from South Africa where I live and work. I studied film directing and screenwriting, so a part of me always knew I wanted to be a storyteller, but my journey was not linear to where I am today. After studying I started working in the film industry as a props master and set decorator for nine years and for a while I really enjoyed this work. I loved thinking about a character and how to visually create the world they live in. To this day I am very intrigued by the aesthetics of the places I photograph in and the people whose stories I tell. I guess this background played a huge part in how I see and think about the world. I especially love creating environmental portraits where a person’s surroundings tell the viewer more about them.

On how your journey in photography

Around age 28 my previous partner and I travelled to Indonesia for six weeks. He suggested we buy a camera and take some photos while travelling, but I thought it was a silly idea and a waste of money. He bought the camera and initially I was very cross with him for using our savings. While in Indonesia I picked up the camera for the first time and fell in love with the medium. I never thought of myself as a photographer or about making a career out of it. Two years later I felt despondent in my career and longed to do more than work on coffee commercials or movies. I had just purchased an old Hasselblad medium format film camera and decided to drive to the opposite side of my country to meet an amazing group of women called the Black Mambas.

The Black Mambas work as an all-female anti-poaching unit to protect our wildlife. I wanted to be surrounded by amazing women doing amazing things as I figured out my next steps and this felt like a good way to do this. I lived in the bush with the women for two weeks documenting their story. During this time, I called the man I had bought the Hasselblad from many times as I was struggling to figure out how to use the camera. Eventually he said to me: “Lee-Ann you have no idea what you are doing, and you will never be a photographer! Please return the camera and I will refund you.” I was furious and ignored his advice.

At this point I knew I wanted to be a photographer, but I didn’t have the means to study so I decided to become a photographer’s assistant. In this way I could learn about photography while having the freedom to work on personal projects. I ended up working for a couple of commercial photographers making work as fashion, product and studio photographers. I always knew I would never become a commercial photographer, but what I learnt was invaluable. Being surrounded by these kinds of photographers had a significant impact on my work. I always knew I wanted to tell documentary stories, but I wanted to craft a visual language and place those stories in a different world. Looking back, I am very grateful for these influences where you are asked to think about lighting and what you want to say with an image. It ultimately shaped my visual style.

People your learned from

During my time working as a photographer’s assistant, I was surrounded by incredible photographers who nurtured my development and became my mentors and friends. It was great to be surrounded by a visual community who could help me grow and help me to find my own voice. I also learn a lot from my peers and contemporary photographers all the time. I try to always reach out to other photographers and make new photo friends. It’s not an easy career path and we can learn so much from each other.

The story of the photos selected for World Press Photo

The project Valim-babena forms part of a larger long-term project called The Big Forget. I have been documenting dementia over the last three years in Namibia, Ghana and most recently Madagascar. The project aims to understand the role of superstitious beliefs and cultural meanings ascribed to dementia to support those living with dementia in Africa.

As life expectancy rises, dementia is becoming an issue globally. According to the World Health Organization, around 55 million people worldwide have dementia, with more than 60% of those living in low- and middle-income countries. In Madagascar, the WHO estimates that some 40,000 people live with Alzheimer’s. Lack of public awareness surrounding dementia means that people displaying symptoms of memory loss are often stigmatized. Many consider the symptoms to be signs of witchcraft, demonic possession, or “madness”.

It often takes me a long time to gain access and set up projects in the various places I have worked. I started discussions with Murial from Masoandro Mody in Madagascar in 2020 and visited in 2023. My projects are often developed over long periods of time and securing funding to work on stories can often be a challenge. I also like to immerse myself in the stories I work on knowing that it takes a lot of time, work and dedication to understand the story you are working on.

Reactions of the jury and public to your project

I really appreciated that the jury chose to include a story like this one in their selection. It is essentially a very quiet story – not something that will make the headlines but at the same time it is a very important story about this time in history. Dementia cases are on the rise and populations are getting older. Sadly, a lot of stories about dementia are still told through a Western lens and less attention is given to understanding how different cultures perceive the disease and more importantly what different communities need to be supported in caring for the elderly.

So many members of the public came up to me sharing personal stories of family members with dementia. For me that is a great moment because it shows how relatable photography is as a medium. We can all understand a picture and relate to the experience of those we are looking at even if our realities are very different.

The entire series of images I made with this family felt incredibly special, tender and intimate. For three years I have been working on this project about dementia and have encountered very difficult moments of stigma and isolation of the elderly. While photographing this family I knew I had found the perfect combination of hope and tenderness despite the difficulties of the situation. This image was very special to me. It felt like an entire story captured in one moment.

The mission of your photos

This story is so universal. It’s a story about family and grief and in a way comments on our own fragility as human beings. The loss of memory and what that means for this family is a story most people can connect to. It’s important to me to highlight stories about dementia in underreported communities.

How you feel winning you 3rd World Press Photo prize

For my work to be celebrated by World Press Photo is a huge honor and privilege. It means that my work gets seen by a large global audience and that the work has a massive reach and can therefore have more impact.

When I think about our history and many of the images I took, I remember they have been acknowledged by World Press Photo. To me this means that this story now becomes a part of our history and something that people will look to and learn from.

What surprised you about the photos selected at Word Press Photo this year

I am always excited to see the selection of images chosen by World Press Photo and more since in recent years since the implementation of the regional model. There are always the images that speak of the year in review and throughout human history we have seen images of various wars and conflicts. This is a sad reflection of where we are at, and it doesn’t seem to be something that will go away anytime soon. There is always a feeling of sadness when I think about how awful human beings are to each other and how that has repeated over and over. It says a lot about our own humanity.

Then there are always unexpected stories of hope, stories that counter history and reveal a new perspective and stories from parts of the world that most people would never visit. These are delightful and provide an insight into creative storytelling. We need more stories like these and the more these get celebrated by spaces like this the more it encourages photographers to tell stories that are not headline news but are equally important.

Back in time, your first photo

I always look back at the photo I made with the old Hasselblad when I visited the Black Mambas with great fondness. Even though I had no idea what I was doing I still made a good picture. One of my biggest lessons in photography has not been the technical skills of how you make a picture but learning that how the person you photograph feels about the photographer is far more important. This is your most important skills because a photo will always reveal how the person being photographed felt about the photographer.

How has the perspective on photography changed for you?

My perspective on photography is always evolving and even the way I think about myself as a storyteller changes. It has taken me a very long time to figure out the best way to tell this particular story. I think it’s especially hard when you start working on a story and you need to take the time to listen and learn and from there you will be able to develop the best visual language for the story. It’s difficult to show an invisible world so you need to think about conveying a feeling and how you can do that visually.

What has photography taught you about people and society

I’m always very aware of the privilege of photographing people and getting access to their lives and stories. Therefore, I always work with a lot of sensitivity and care and when I first meet a family, I work slowly so that I take enough time to look and listen. Just because you own a camera it doesn’t mean you have the right to use it. I am always amazed at how openly people share some of the most intimate parts of their stories with us. Therefore, it is a great responsibility and we become the guardians of the stories entrusted to us.

A few weeks before my visit to Madagascar my father was diagnosed with a very aggressive form of dementia. Being around Muriel and the team from Masoandro Mody helped me to process my feelings and ask questions while we as a family were taking the time to figure out the best way to care for my father. Being surrounded by such a sensitive and supportive community showed me what families need in order to care for the elderly and how Masoandro Mody was playing a key role in not only supporting the person living with dementia but also family members and carers. As storytellers we grow with our stories and our personal experiences inform the way we work.

The themes you currently explore throughout photography

I am always interested in stories about people and most of my work focusses on themes of gender, identity, education and health.

As a female photographer it’s important to me to tell stories about women from the African continent where I live and work in a way that is affirming and celebratory. Even when documenting difficult social issues, I have no desire to show people at their weakest moments. I want to show people’s resilience and how solutions are being found from within the communities facing challenges.

The messages of your stories

I want to tell stories of hope and I want to use the medium of photography as a mode of celebration. I feel deeply connected to all aspects of life through photography and for me it is a way to process and experience all the joy and sadness that make up this human experience. It’s a way to connect with others that I am perhaps not able to do in everyday life. I am incredibly shy, and I know that my camera is a passport to different communities and experiences. Therefore, I always try to treat this privilege with great care and respect.

Your perception on our image-obsessed world and everyone taking photos for social media

We are constantly bombarded with images and in this time, where even the most important images enjoy a very short amount of screentime, in the world before the next story gets shared, I think it’s more important than ever to make work that sticks, and that people will remember.

The role of photography now

In the age of AI and disinformation photography is more important than ever. Journalism is constantly under attack and the state of press freedom is more dire than ever before. At its worst, photography can be used to divide and used as propaganda. At its best, it can inform and connect us to something bigger than ourselves.