Instead of "Look at me and my great work!" it's better to ask: "How can I be of help? What can we do to make a difference in this world?". This is the guiding thought behind Matthias Hillner's work. Matthias is Professor at the SCADpro Department at The Savannah College of Art and Design in the USA. His role involves guiding interdisciplinary student teams who develop design innovations and start-ups in exchange with industry partners.

Matthias relocated to Singapore to become Head of School, Design Communication at LASALLE College of the Arts in 2015, and he served as Director of Programmes at the Glasgow School of Art Singapore from 2019-2021. His areas of specialism comprise communication design, experience design, service design, creative leadership, and design innovation management. He holds three postgraduate degrees from the Royal College of Art and has authored two books: Virtual Typography (2009) and Intellectual Property, Design Innovation, and Entrepreneurship (2021).

"I had to change perspective, expand my horizon of experiences, review my priorities and value systems. Therefore, I no longer ask myself: How are things? I explore: How do things change? To grow with design and through design means to ease into the rhythm of change, and to find comfort in it", says Matthias.

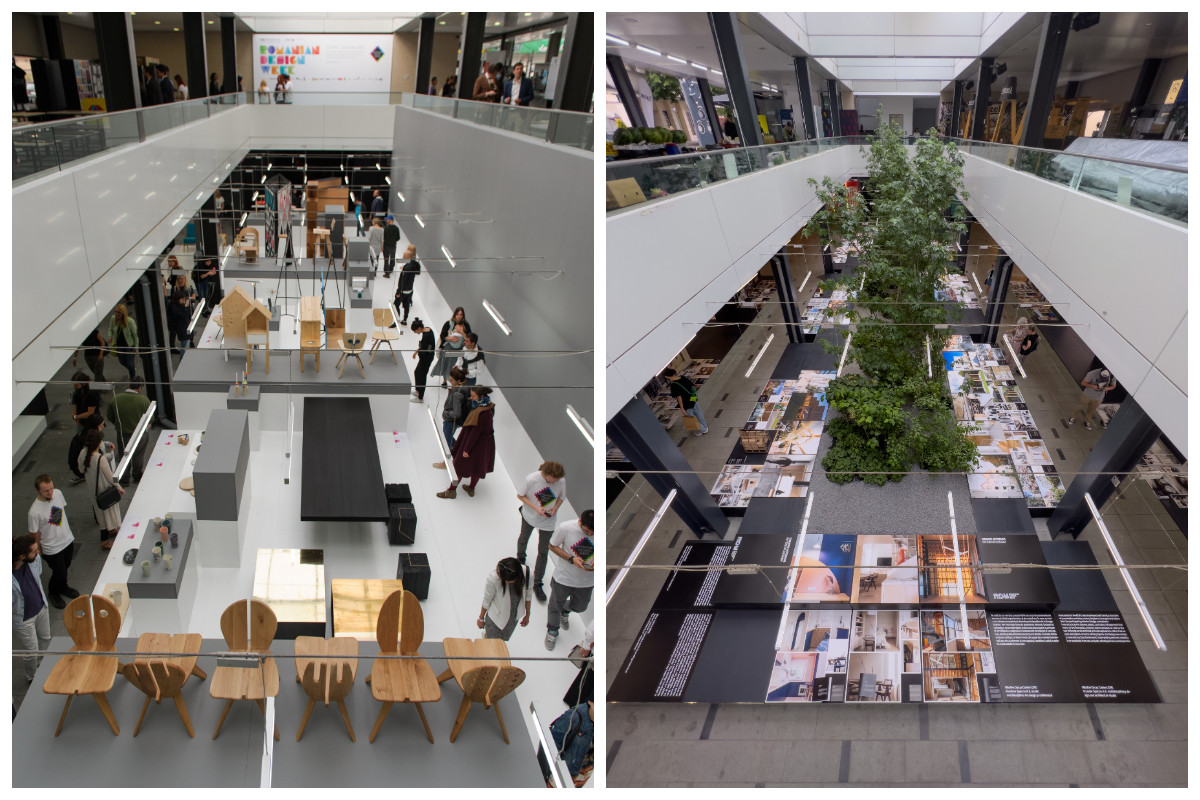

Matthias Hillner is the curator for the Product Design category at the 12th Romanian Design Week, which takes place from May 24 to June 2 in Bucharest. Under the theme "Unlock the city", RDW showcases over 200 projects from 6 different categories: architecture, interior design, fashion design, graphic design, product design, and illustration.

We talk to Matthias about his design journey and the lessons he's gathered with each chapter of experience, how his perspective on his role as a creator has changed, and what are the important transformations influencing the creative industry in 2024.

Important chapters in your experience

Advertising and Design — What on Earth is Creativity?

From advertising photography to graphic design — In the early 1990s I worked in car advertising photography in Germany. Some of my employers had invented their own lighting system securing monopolies surrounding their technologies. However, as far as advertising photo productions are concerned, I realized there was a fair amount of semantic stereotyping at play in terms of the settings. Advertising agencies amplified the evocative imagery through catchy slogans. It was fascinating but also felt a little empty.

When switching to graphic design in the mid 1990s, I was introduced to corporate identities, information design, and multimedia technologies. The Ulm School ethos which I found myself immersed in, was hyper-rational, very intelligent, but it was also quite dogmatic and uniform. It was intellectually stimulating, somewhat sobering, but I missed the magic of light, perspective, and atmosphere.

Originality — Toward a Sense of Self

In the late 1990s I joined the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London, UK, eager to find a way to unite the atmospheric qualities that had fascinated me in photography with the systematism I had adopted in the context of modernist design. I experimented with light, abstract photography, typography, motion graphics, and I began to read philosophy. Technologies gradually allowed to simulate virtual environments with relative ease, and I explored the limits of these technologies to find out how three-dimensionality and movement in the digital sphere can be used to lend typographic compositions atmospheric qualities. As internet bandwidths were insufficient to carry multidimensional motion graphics in those days, there was limited scope to commercialize these novel approaches.

Design Experimentation and Research — Between Ideologies and Pragmatism

From 2000 to 2010, I split my efforts between design experimentation, commissioned work, and design research. It was a constant balancing act between mainstream practice and avantgarde explorations. I began to teach design, because this allowed me to be more selective in terms of design commissions and other engagements. A successful business startup pitch allowed me to set up my own design studio which I developed in tandem with design research. I realized that research can be creative and rewarding, and that it can significantly advance design practices, if done well.

From Design to Creative Entrepreneurship — Taking the Plunge

The decade after that was really a drive towards innovation. I engaged in several R&D projects and developed a strong interest for creative entrepreneurship. In British design education entrepreneurship was a bit of a buzzword at the time, and, whilst many universities jumped on this band wagon, few knew what entrepreneurship and innovation really meant, or what it involved. I played with the thought of doing a PhD, and before I realized, I was already enrolled for a PhD at the RCA’s Service Design Department. This was profoundly transformative. Although I spent initially still four or five days teaching visual communication, I gradually immersed myself in this new emerging field. There were no more than three service design courses in the UK, and innovation was stronghold in engineering and in business rather than in design.

Innovation Management — Taking an Even Bigger Plunge

Having given talks and workshops in numerous countries, mostly about typography and media design, I decided to accept an offer to move to Singapore to work in the city state from 2015 onwards. Here design was better connected to innovation than in other parts of the world, and I worked in close exchange with industries and government agencies who were eager to push Singapore’s innovation capacity. Singapore’s Design 2025 masterplan had just been freshly baked, and the city was a useful base for me to extend my design innovation research in London and Europe into the APAC area.

Creating Value for Others — From Design Startups to Corporate Innovation

When Covid hit, the world was turned upside down, and innovation activities slowed down. I moved to Cambridge, UK, hoping to push innovation opportunities there. However, I came to realize that the innovation ecosystem in the UK was hit even harder than Singapore’s. I joined the SCADpro at Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), a cross-disciplinary department that is dedicated to developing high-impact innovation solutions for SCAD’s corporate client partners. Here I have got the opportunity to teach innovation principles, and to work with interdisciplinary student teams on commissioned projects. We help large and small organizations with design solutions. My projects range from architectural developments, to metaverse experiences, and service system designs, and I typically oversee two or three projects at a time.

Your perspective on design

In the beginning of my career, I searched for certainty and stability. I have come to realize that stability is an illusion. Everything changes continually and increasingly rapidly. Over the years, I have found comfort in the idea of change. Having realized that the design industry, too, is constantly changing, I wanted to help to try to pro-actively drive this change, and that meant that I had to change myself from time to time.

I had to change perspective, expand my horizon of experiences, review my priorities and value systems. Therefore, I no longer ask myself: How are things? I explore: How do things change? To grow with design and through design means to ease into the rhythm of change, and to find comfort in it. Understanding change allows us to identify new directions, the pace of change, and its nature. This in turn allows us to become thought-leaders, and, once we understand the nature of change and the fundamentals of transformation, we can drive these processes.

Another key perspective change is the shift away from the individual towards the collective. Having worked for famous and wealthy photographers and celebrated designers, I initially sought to become like them. Thankfully, the era of stardom and celebrities had come to a halt by the time I was ready to make my mark in the industry.

Dropping ideas of fame and excessive financial gains, allowed me to remain exploratory and observant of others as well as the world around me. In the early 2000s my emphasis shifted towards collaboration and innovation, not-least through working in Asia. Here I developed a stronger sense of the value of collective efforts, societal needs, and collective gains. My perspective became a lot more systemic, and this enabled me to engage with much more complex issues such as sustainability and experience design, and to manage co-creative processes. Instead of Look at me and my great work! the guiding thoughts were How can I be of help? What can we do to make a difference in this world?

Your beginnings as a designer: expectations & fears

No expectations, no fear. I was full of curiosity and excitement. Having started my career journey in advertising photography and sought to become an advertising creative. I happened to join a university who focused on identities, information design, and multimedia. Thus, I was dragged into a quite different direction — thankfully. I was good at photography, and realized everybody else was better in typography, something I knew next to nothing about. Instead of building on my strengths, I decided to challenge myself, and to focus on honing my typography skills. I find it important to iron out my weaknesses and to widen my horizon. This allows me to continually grow, both as a professional and as a person. Stepping outside your comfort zone is very important for personal growth. Through confronting ever-larger challenges, we develop both capacity and confidence.

What has fundamentally changed in your relationship with design

Everything and nothing. Thirty years ago, I worked on car advertising photoshoots in Germany and in Greece, now I am working — amongst other things — on the Innovation Strategy Blueprint for BMW America. All the experience I have gathered over the years is valuable — graphic design, media communications, product innovations, service design…

I feel that conceptual thinking and creativity do not know any boundaries and can be carried across disciplines. It is curiosity that drives us, it is curiosity that brings us together. There is always something new to be discovered. Contexts change, questions change, the principles remain the same. That said, I do believe that is important to recognize is A) the implications of the fourth industrial revolution, and B) the growing challenges we are faced with on a global scale. This means that our approach to design must be systemic in nature and much more innovation oriented. We need to take into consideration the impact our actions have on the environment, on people, and on societal structures.

Product Design in 2024

There seems to be a fairly contrasting picture: It is almost as if designs are conceptually more or less conventional and beautifully crafted, or they are conceptually interesting but much less developed. Ideally both aspects are covered to a very good extent. There are some works which raise questions, which I found fascinating. Some of those were material explorations, others were artistic provocations, and yet another range of designs explored new areas of design opportunities, for example a product that can function both as a fence and as a seating option. Although not all those submissions made it into our final selection, the thinking behind these daring ideas is to be applauded. As inventors, we need to embrace failure before we can expect to touch on something that stands the test of time. Designs that lead to quick success, are hardly ever of transformative impact.

One point I would like to make with a view on the future of product design in general, is that product designs ought to be conceived as system components and experience enablers. Products are continuing to become less physical, as is perhaps human behavior. For example, Gen Zs do not value cars in the same way as former generations did. Notions of status and identity no longer revolve around physical objects and possessions. Communication, virtual connectivity, and recognition have become the driving factors. We see products increasingly embedded in experience or service systems. If conceived as parts of systems, product designs can be significant drivers of change.

The good parts. And the bad

We saw a good amount of great craftsmanship amongst some design solutions which were more conceptually driven, sometimes even thought-provocative. This is good. We need designers to question existing conventions, and to approach design opportunities in an inventive way. During the briefing we touched on the notion of eclecticism. I perceive this as a good characteristic, in particular if paired with exploratory, experimental approaches. There was a fair amount of tinkering involved in the design processes.

Sometimes the explorations could — perhaps should — go further. Whilst it can be useful to be playful at the outset of a design initiative, it is important that designers wrestle with their solutions thoroughly, and that they pay attention to detail, materials, production, and finishes. One almost wants to switch mindsets halfway through the process. Starting out in a playful, improvisational fashion, one needs to become a perfectionist when it comes to the process of refinement and finishing.

Curating at RDW 2024

All in all, I was pleasantly surprised with the range of work and with the quality. There was a lot of very good work, and the curatorial process was exceptionally well organized. Working in exchange with Alexander Manu is always rewarding. We have exchanged very regularly and intensively on design and innovation throughout the past few years. Curating a showcase together allowed us to explore how we apply our perspectives on design and innovation in practice. I am looking forward to visiting Bucharest for the first time, to see the works for real, and to continue our conversations.

In a recent exchange, Alexander Manu pointed out that “innovation is a culture”. This resonates with most, if not all my other recent conversations with innovation advocates. Design is a process, but also a reflection of the cultural heritage of a society. Cultural developments need to be initiated and carried through groups of people, not individuals. This is why exchange is so important. Through critical discourse and ideas sharing, you align perspectives and inspire one another. Ultimately Romania has its own history, characteristics, and needs. Design communities can shape values and principles which can drive societal processes. RDW strikes me as a perfect platform for transforming culture and society.

Changing Role of Creators

This is a very interesting question. The significance of creativity is increasing due to pressing needs and the challenges we are faced with in the 21st century. I see two trends emerge: For one, there is an increasing need to infuse creative capacity in non-design areas such as technology, science, business, corporate governance, politics, etc. This means that we will see designers work in roles that are not by default design related.

A good number of former students of mine work in the innovation departments of banks, insurance companies, in housing, public transport, medicine, etc. Secondly, there is a need to empower non-designers to engage pro-actively in creative processes. This means that designers need to be enablers, educators, collaborators, and innovation catalysts. I foresee design and innovation to blend more strongly with other professional practices and walks of life.

How do you adapt to these changes

I change with them and grow through them.